Just four cents per DVD — that’s the writer’s home video residual, we’re told. More specifically, the hated DVD formula is 1.5% (or 1.8%) of 20% of the studio’s gross on DVD sales. That odd looking set of percentages is equivalent to 0.3% or 0.36% of the studio’s gross. The 1.5% or 0.3% applies when the studio’s gross on a title is less than or equal to $5 million; the 1.8% or 0.36% applies thereafter. If the studio gets about $11 on an average $22 DVD, the writer(s) get a total of three to four cents.

That sounds small, and it is. The WGA made a proposal to double those residuals — that would be a four-cent raise per DVD — then withdrew the proposal at a bargaining session two weeks ago. Now the proposal may or may not be back on the table when talks resume next Monday, but even eight cents per DVD sounds modest. Why are studios resisting?

Then there’s new media. Here, the Guild is looking to double its take on streaming (from 1.2% of studio’s gross to 2.5%) and an eight-fold (not eight cent) increase on downloads (from 0.3% of the studio’s gross to 2.5%). That last one is large in relative terms, but the actual dollar amounts are small today (though will be larger in the future). Hence, again, the question: why are the studios fighting the Guild so vociferously?

The answer on DVD dates back to what many of us inadequately learned in third grade: multiplication. On new media, throw in a bit of geometry as well. What are the facts and figures, and are they persuasive? Here’s the 411.

Multi-Guild Residuals — Almost Ten Times the Fun

A four-cent per DVD increase sounds like a no-brainer. But in the world of Hollywood unions, four cents is actually almost forty cents. This is true for a simple reason: the WGA isn’t the only union in town.

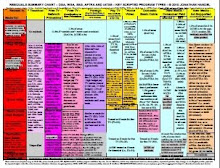

As it turns out, all three guild agreements (WGA, DGA and SAG), plus the IATSE agreement, have similar DVD residual formulas. Any amendment to the WGA’s DVD formula will almost certainly be made to the other unions’ as well. It’s called pattern bargaining; the deal for one is the deal for all — but with a twist: SAG’s formula is three times as large as the WGA’s, and the IA’s is four and one-half times as large. (The DGA’s is the same as the WGA’s.) New media formulas can be expected to mirror each other across unions in the same fashion.

So, if writers get a four-cent raise, actors get an extra twelve cents. That’s not because actors are three times better than writers, but because there are so many more of them on any given movie or TV program. The actors split the residual among themselves based on a formula that reflects both salary and time worked on the show. Thus, each actor’s share is less than the writer(s)’ share. (Writers too have to split among themselves when there’s more than one writer on a project.)

The DGA raise would match the writers’ — four cents. Most of that would go to the director. Yet, 40% of the DGA membership are below-the-line workers who receive a miniscule share of DVD residuals (less than one-fifth of a penny per DVD). Doubling the formula would make little difference to them, which is one reason why DGA support for a strike over residuals is so tepid.

The IA raise would be 4.5 times the writers’ — an extra eighteen cents per DVD — yet IA members receive no residuals directly. Instead, the residuals are used to fund the IA’s health and pension plans. So, residuals matter to IA members, but in an attenuated way.

Bottom line: whatever increase the writers achieve in DVD or new media has to be multiplied by a factor 9.5 to determine what the studios will be paying out. (9.5 = 1x for the WGA, 1x for the DGA, 3x for SAG, and 4.5x for the IA. If you want to read the contract language for yourself, check out the WGA agreement (Art. 51.C.1.b), DGA agreement (Sec. 18-104), SAG agreement (Sec. 5.2.A.(2)), and IATSE agreement (Art. XXVIII(b)(2)).)

DVD — The Shiny Little Disc Just Keeps Spinning

How do these numbers play out in practice? The studios and the WGA each have their own numbers, and so far as I know, are not releasing them publicly. But we can take a stab at it.

Start with DVD. Let’s reject the conventional wisdom that physical media don’t matter. DVD is a $16.5 billion business (domestic sell-through in 2006). That’s a far bigger business today than downloads and streaming (see below). When the Blu-ray / HD DVD format war gets resolved, people will probably start buying more product, and that number will spike up. And in the more distant future, even if discs are replaced by chips, holographic data storage, or little nano-somethings, the “DVD formula” — i.e., the home video formula — will still apply. So, the formula matters.

Now let’s do the math. $16.5 billion retail gross equals an approximate $8.25 billion gross to the studio (assuming a 50% margin). Multiply by 0.3% or 0.36%, yielding a $24.75 million to $29.7 million single-guild residual. Multiply by 9.5, to arrive at a 4-union figure of $235 million to $282 million. Now, multiply by 3 — the guild and IA agreements are three-year contracts — to arrive at a $705 million to $846 million cost over the term of the contract.

This calculation assumes that the DVD business (standard def plus Blu-ray and HD DVD) neither grows nor shrinks materially over those three years. This was true of 2006 as compared to 2005, and some analysts predict little growth over the next few years (see chart in 12/19/07 print edition of LA Times, p. A15; not available online). I believe the actual figure would be higher if one of the high def formats takes off, but that’s unlikely unless and until one of the formats prevails and the other drops by the wayside. When, or even if, that will happen is anyone’s guess.

The WGA wants to double the residual, which would add an extra $705 million to $846 million cost to the contracts, whereas the studios want to keep the formula unchanged. So, the parties are $705 million to $846 million apart on the issue of DVD residuals.

Let’s look at the numbers another way. Can the studios afford to increase the DVD residual? Yes. There were 1.3247 billion units of DVDs shipped in 2006. $16.5 billion divided by 1.3247 billion units yields a mean (average) price of $12.45 per unit. The cost of manufacturing a DVD in quantity, including insert, packaging and shrink wrap, is frequently quoted to me as only $0.25 - $0.35. That leaves a lot of profit ($12.10 - $12.20). But, there are also marketing and distribution expenses. One well-regarded book (p. 130) estimates manufacturing, marketing and distribution costs at “less than $5 per unit.” That implies net receipts per DVD of about $7.50. A $0.38 increase in the residual is a 5% additional cut out of $7.50.

However, from this $7.50, we should deduct some allocation of the cost of production of the film. How much this allocation should be is hard to determine. For one thing, it depends on the negative cost of the film. This, of course, can vary widely. In addition, there is probably some correlation between negative cost and DVD sales, but this would be contained in proprietary studio models which I don’t have access to (and which would be protected by confidentiality agreements in any case). How strong this correlation might be is unclear in any case.

Also, there might be some correlation between negative cost and DVD manufacturing, marketing and distribution costs, since negative cost might correlate with the quantity of DVDs manufactured, and also with how elaborate the packaging and insert might be. (Clearly, there’s correlation between these latter items and domestic box office, since studios will spend more on the DVD for a successful movie; but whether there’s also a correlation with negative cost is less certain.)

In addition, deciding how much of the negative cost to allocate to the DVD revenue, as opposed to how much to allocate to theatrical and other revenue streams, is somewhat arbitrary. Should all of the negative cost be allocated to theatrical, since this is the initial market? Should the allocation be proportionate to the revenue received from each window? Or should the allocation proceed in some other fashion?

So, that $7.50 figure has to be reduced, perhaps significantly. Thus, the $0.38 increase in residuals represents a greater than 5% additional cut of the studio’s net, perhaps significantly greater. Conclusion: on some DVDs, a $0.38 increase might be too high to be reasonable, but it’s hard to tell. So, it’s probably appropriate for the Guild to settle on some compromise between leaving the residual unchanged, on the one hand, and doubling it, on the other. This is why I have previously proposed a 1.25x – 1.5x increase.

New Media —Now Playing on a PC and Cellphone Near You

On new media (streaming and downloads), much of our work is already done. Using various research data, Michael Learmonth has estimated that the parties are $7.2 million apart in 2007, with that gap increasing to $71 million in 2011, on a single-union basis. Assuming for the sake of simplicity that the growth between then and now is linear, this results in a single-union three-year gap of $117.6 million ($23.2 million in 2008, plus $39.2 million in 2009, plus $55.2 million in 2010). Multiply by 9.5, to arrive at a 4-union figure of $1,117 million. Michael’s figures don’t include revenue from banner ads and subscriptions, which the WGA rightly wants a piece of. Those revenues are probably larger than the revenue from in-stream advertising (ads in the videos themselves) — though who knows — so I would at least double this figure to $2,235 million.

Can the companies afford the increase? Yes. Distribution costs are negligible, since there is no manufacturing cost, and marketing costs can best be described as moderate, since films and TV shows have built-in name recognition (no need to spend astronomical sums to drive traffic to the company websites). Even after allocating a portion of negative cost to new media, the companies’ profit will ultimately be quite high. This is why execs have been effusive in their embrace of new media and their predictions as stated to Wall Street.

Divide and Conquer

Adding the home video and new media gaps yields a total gap of about $3 billion on the residuals issues. That’s more than the pocket change implied by “four cents per DVD” — or is it? After all this multiplication, now it’s time for division. Divide by 8, yielding $375 million as a per-company average, to roughly account for the fact that there are six majors, one quasi-major, and many smaller companies in the AMPTP. Then divide by 3, yielding a gap of $125 million per major per year.

Remember too, the WGA doesn’t realistically expect to get all the numbers it’s asking for; a negotiation is a compromise, not a diktat. Let’s assume the parties split everything down the middle. That’s about a $60 million increase per major per year. $60 million? It’s a small fraction of the typical revenue and profits the conglomerates are achieving. The numbers are complex, but the conclusion is simple: the producers can afford to increase the residual payments, and it’s time for them to do so.

PS: The LA Times (11/19/07, p. A15) has new media numbers that are slightly higher than Learmonth's in 2007 and significantly lower in 2011. The difference on a per-studio per-year basis is not great.

Also, note that the above article only discusses residuals. The WGA proposal also includes an increase in minimum compensation rates for film and TV writing, and a request for jurisdiction over writing for new media. Both of these requests increase the studios' costs by an amount that is difficult to determine.

Oh, a couple definitions might be helpful too. "Negative cost" means the cost of making a movie, including writing, development, preproduction, production and postproduction.

Negative cost does not include the costs of distributing a movie theatrically (such as the cost making prints of the movie and paying for advertising, marketing and publicity -- so called "prints & ads" or "P&A") nor the cost of releasing a movie on DVD or television.

"Majors" means the six major studios - Disney, Fox, Paramount, Sony, Warner Bros. and Universal.

The quasi-major I refer to in the article is MGM, which was once a full-fledged studio with its own studio lot and an extensive library (catalog) of films. It now has, instead, an office building and a small library, but retains some other attributes of a studio.

I also mention in the article that there are many smaller companies in the AMPTP. More precisely, there are many smaller companies that are signatory to the WGA Agreement. Not all of these companies are actually members of the AMPTP, but the distinction makes no difference to the economic analysis. A list of signatory companies can be found at http://wga.org/subpage_member.aspx?id=2537.

This article originally appeared in The Huffington Post on November 23, 2007.