AFTRA, a

First, if you’re just tuning in to the

We’ll blaze through what’s happened to date. Skip the numbered paragraphs if you’re already au current.

1. Negotiations last year between the writers (the Writers Guild of America, or WGA) and the AMPTP (Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, i.e., the studios), over revisions to the contract expiring October 31 last year, began in earnest at the end of October and collapsed at the beginning of November, largely due to studio intransigence.

2. The writers went on strike Nov. 5.

3. Negotiations restarted in December, but promptly collapsed again, for the same reason as the early go-round.

4. The studios began negotiations in January with the directors (the Directors Guild of America, or DGA) – whose deal was not expiring until five months later – and reached agreement that month.

5. The studios resumed negotiations with the writers, this time sending several studio heads, and reached agreement in February. The writers agreement achieved a few, relatively small improvements over the directors deal.

6. The strike ended and the deal was approved in mid and late February, respectively (two separate votes about two weeks apart).

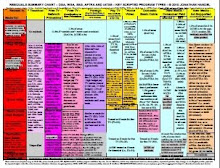

Now it’s time for the actors, whose deal expires June 30 (the same date as the directors deal was set to expire). The Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA) jointly negotiate the film and primetime TV deal, primarily found in a contract called the SAG Codified Basic Agreement. This joint negotiating posture is called Phase One, because it’s supposed to be the first phase in an eventual merger of the two unions – something that SAG has repeatedly rejected, however.

The two unions have 50-50 representation on the bargaining committee, even though AFTRA jurisdiction includes no films (so far as I’m aware) and only three primetime series. SAG has 120,000 members, AFTRA 70,000, and dual members (“dual cardholders”) constitute 40,000 of those two figures.

What about daytime TV shows? They’re under sole AFTRA jurisdiction, and subject to a separate contract, called the Network Television Code. (Exhibit A of the Code covers primetime, and basically cross-references the SAG agreement.) In general, SAG covers filmed productions and AFTRA covers tape, with digitally-shot productions subject to overlapping jurisdiction, but this is said to be something of an oversimplification.

More specifically, SAG covers the big ticket items – primetime shows, episodic cable shows (i.e., scripted dramas and comedies), and films. AFTRA covers syndicated dramas, daytime serials, game shows, talk shows, variety and musical programs, news, sports, reality shows, and promotional announcements.

SAG board member Justine Batemen describes the jurisdictional breakdown as follows:

“SAG has work that is recorded, no matter the medium upon which it is recorded, for later play (sitcoms, dramas, films) and AFTRA has live shows (newscasts, talk shows, etc.) and those recorded in a "live manner" (awards shows, Saturday Night Live, and then variety shows and soap operas which used to be live).”

The two unions have very different positions on the proper relationship to management (which is one reason that past merger attempts have failed). SAG’s national leadership – headed by president Allan Rosenberg and National Executive Director Doug Allen – and its

In contrast, AFTRA – led by Roberta Reardon, AFTRA President and Chair of the Negotiating Committee and National Executive Director Kim Roberts-Hedgepeth – usually takes a more conciliatory approach to management, and feel that aggressive tactics simply drive more production to go nonunion, or to flee to Canada, where U.S. union minimum wage scales don’t apply. SAG

SAG, reflecting its assertive approach, has refused to begin negotiations on the expiring agreement until April. This, they feel, will give them maximum leverage. That’s because mid-April is the deadline for what’s referred to as a de facto strike. This is the date past which few films are being greenlight for start of production. That, in turn, is because a typical film production schedule provides for 60 days of principal photography (i.e., shooting). April 15 plus 60 days equals mid-June. Any films started later than mid-April would risk having actors walk off the set come June 30, if a strike materialized.

In contrast, AFTRA, and a group of prominent actors such as George Clooney, wanted negotiations to begin immediately. In the last day or so, it appears that some fence mending has occurred, and the unions will negotiate jointly, but that talks will start in April.

SAG has identified three or four areas on which they’ll focus in negotiations on the Codified Basic Agreement. In addition, of course, there are always a host of other issues in any union negotiation, but the ones identified here are likely to be the most contentious.

First, they want improvements over the WGA deal in new media. Bateman identifies two aspects of the deal as inadequate: the WGA deal (which I summarize here) has a 17-24 day window during which no residuals are payable for ad-supported streaming of new television shows (she feels this is unfair, and wants no window); and there are budget floors below which certain shows produced for new media are not covered by the union agreement (she feels this will create a pool of non-union actors, but doesn’t specify whether she wants lower floors or none at all). I’m guessing the studios left themselves enough headroom to give a little on these issues, allowing the actors to ultimately claim a victory.

The second area in which SAG wants improvement is the conditions for middle-class actors. It’s unclear if this means SAG is seeking significant increases in minimums – i.e., even greater than the typical increases – or if they’re looking for something else (or both).

The third area is forced endorsements. This refers to product integration, which is product placement on steroids. Product placement means a product appears passively on screen in a film or, increasingly, a TV show; for example, a Coke bottle appears on the table during a scene. Product integration, which has become more prevalent lately as the film and TV business have become economically tougher, means that the product is touched by an actor – he or she drinks the Coke – or is referred to verbally, e.g., the actors asks for a Coke. It also mean the situation where a product or service appears pervasively in the film or TV show, i.e., repeatedly.

In both product placement and product integration, the production company receives either a payment from the brand (i.e., the product manufacturer) or consideration in kind. These latter, referred to as barter deals, entail the brand giving product or services to the production company. For instance, an airline featured in a film might give air tickets, allowing the production to fly to locations at no cost when the film is shot in various cities. Product placement or integration deals can also be hybrids, involving both cash and goods or services.

Currently, actors do not receive any compensation from product placement or integration deals. Their concern focuses on product integration, and is several-fold. One issue is that, having touched or called for a product by name, they no longer have a chance to do a commercial deal with the product’s competitor(s). or instance, an actor in character who calls for a Coke can scarcely do a Pepsi commercial.

Secondly, the further value of the actor to the integrated product is reduced. For instance, the actor might get a Coke deal, but it might be at a lower rate than on the open market, because the brand already has footage of the actor (in character) calling for a Coke.

Finally, the actors are unhappy that they (in character) are being used to sell a product and garner revenue for the production company, yet not sharing in the bounty. For instance, a famous actor is hired, in part, to attract an audience, and he or she shares in the (hoped-for) success of the film or show through residuals and profit participations. Likewise, goes the logic, if famous actor attracts a brand to do an integration deal, they want to share in that success as well.

A fourth area the actors indicated they want improvement over the writers deal is DVD residuals. These rates (percentages) have been low since 1984, when the directors accepted what the writers and actors view as a bad deal, one which has persisted to this day, as I explain here. SAG president Rosenberg mentioned this issue in January, but his more recent statement of issues that SAG will focus on omits DVD residuals, and lists only the first three issues. Thus, it’s unclear whether SAG will emphasize this issue, and it’s unlikely they’d get much traction on it, now that the other two unions abandoned attempts to reopen a quarter-century old deal. That’s unfortunate, because the DVD formula will continue to matter for decades, as I discuss here.

The AFTRA deal announced yesterday includes provisions on new media residuals and on jurisdiction over content created for new media (as well as increases in traditional media minimums, and new or revised approaches to a host of other issues). I’ve been informed by an AFTRA spokeswoman that the deal tracks the writers’, but details have not been announced yet, so it’s unclear what differences there might be.

Two other SAG issues are in the mix. One is whether the Phase One joint bargaining relationship will collapse, leading to two separate negotiations of the film and primetime agreement. This would dramatically undercut SAG’s leverage, since producers would presumably be able to do less expensive deals with AFTRA.

The other issue is qualified voting. This is the concept that membership voting for a strike or voting on the new contract, when a tentative deal is reached, should be restricted to members who have worked at least a minimum number of days (or earned a minimum amount) from acting in a given year. This is a concept being pushed by moderates, who fear that less-employed or unemployed actors (who constitute a large percentage of the union) are more likely to vote for a strike, having less to lose (since they’re not, or are scarcely, working anyway).

Reportedly, the SAG Board could institute this system, but I think it’s unlikely to do so, precisely because it would reduce the likelihood of a strike (and thus SAG’s leverage) and because any Board member who voted in favor of disenfranchising a large number of members would be voted out of office next election.

So what happens next? I think we’ll see a de facto strike starting in April – indeed, we already are, as a number of films have been postponed, and few are being greenlit already for production starts after mid-April.

We may also see a strike authorization vote, which would then allow the SAG and AFTRA Boards to call a strike without further membership vote (assuming this process is provided for in the bylaws of those unions, which I’m not sure about). I think a strike authorization vote will probably only occur if talks in April are not promptly fruitful.

The big question is whether we’ll see a strike. Everyone wants to speculate on this one … but it’s simply too early to predict. I think we do have to take the prospect seriously though, as studios already are. Stay tuned.